Researchers in Biological Sciences at Birkbeck, in collaboration with a group at the Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre in Melbourne, have determined the structure of a protein assembly used by the immune system to kill unwanted cells. The immune system uses cytotoxic T lymphocytes and natural killer cells to act as executioners when it detects the presence of virally infected or cancerous cells. The cytotoxic and killer cells contain small membrane parcels filled with the protein perforin, which can punch holes through cell membranes, along with the toxic granzyme enzymes. When an infected cell is detected, the killer cell latches onto it and ejects some of the membrane parcels with their toxic contents so that the perforin protein punches holes in the target cell membrane, through which the toxic granzymes enter, rapidly causing the target cell to die (Figure 1). The cytotoxic and killer cells are professional assassins that can kill many victims in rapid succession, briefly attaching, ejecting their lethal cargo, and then moving on to the next victim. Perforin is an essential protein for survival, and unfortunate individuals who lack functional perforin usually die of infection or cancer in early childhood. On the other hand, over active killer cells can also cause serious damage, by triggering inflammation and killing healthy cells.

A former postdoctoral researcher, Marina Ivanova (now at Imperial College), determined the perforin structure in the group of Professor Helen Saibil, and the paper has been published in Science Advances. Perforin is made as single protein molecules that are stored inside their membrane compartment until they are needed, but when they are released, they join up into rings of around 22 molecules and undergo a dramatic shape change in order to punch the hole through the target membrane. Two parts of the protein that are at first coiled up in the molecule extend and join up into the ring to punch through the membrane. This shape change is shown in Figure 2, with the part of the protein that makes the big change highlighted in pink.

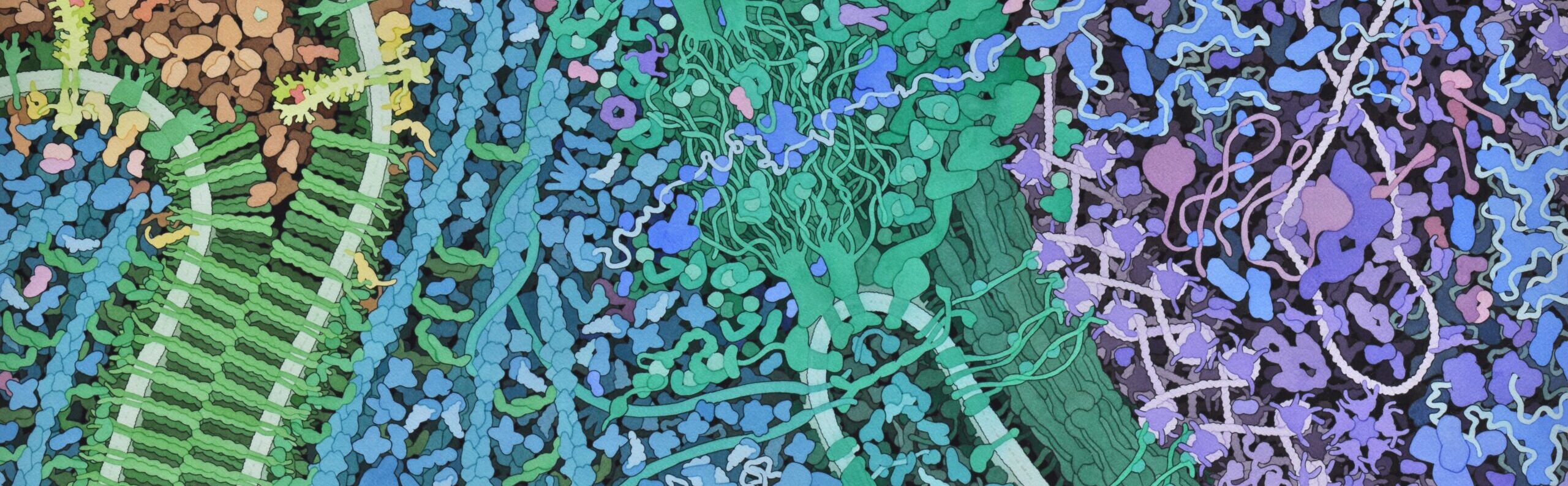

Figure 3 shows two views of a perforin ring (multicoloured molecules) enclosing a hole in a cell membrane (shown as a pale blue slab). Now that we know the details of the pore structure, it will be possible to think about designing drugs to either enhance or prevent its activity. This could eventually lead to new therapeutics for certain autoimmune diseases and the condition familial hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis.